Friday, May 28, 2021

Barry & Shelton

Thursday, May 27, 2021

Community service opportunity

Focus on Melrose: the Morse brothers

Focus on Melrose: Phineas Upham

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Melrose Spotlight: the Bungalow

Friday, May 21, 2021

Mystery in the Highlands

Thursday, May 20, 2021

Research the history of your home - tutorial five: Newspapers

Tuesday, May 18, 2021

Lost Melrose, Volume Eight

Monday, May 17, 2021

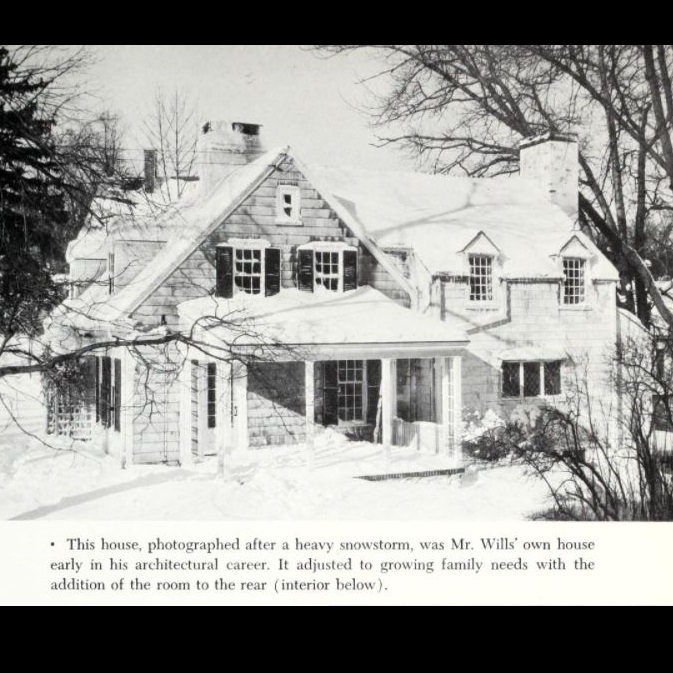

The Colonial Revival style and Royal Barry Wills

Thursday, May 13, 2021

Lost Melrose, Volume Seven

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

Melrose Spotlight: the Triple Decker

Tuesday, May 11, 2021

Research the history of your home - tutorial four: Headstones

It is time to return to our sources series, to discuss a weighty type of document: the headstone. Is it worth pursuing the record of the people who lived in your house to the grave? In general, yes.

Some gravestones do not tell us much. The earliest stones tend to be highly stylized: first death’s heads, then cherubim, then urns. In the second quarter of the twentieth century, the stones again became standardized, set in rows, and usually yield no information other than names and dates.

But the Victorian era, lasting roughly from about 1840 to the start of World War I, gave us stones that have as much variety as the houses of the same period, and can tell us a lot about the values of the people who had them carved. Liberty Bigelow, for example, not only wanted to turn his house, today’s Beebe Estate, into a showplace, but paid to have the tallest monument in Wyoming Cemetery, an obelisk over two stories tall. Moses Page was a successful Melrose businessman who was neither Catholic nor Irish, yet he insisted on an elaborate Celtic cross as his memorial—which raises new questions about him. The parents of little Italo Americo Giacobbe memorialized their three-year-old son with the carving of an angel—and the very fact that this poor immigrant couple chose to spend their savings on this stone tells us something significant about them.

Not everyone in Melrose got a stone here. There are no surviving stones for enslaved people. Pauper’s graves, of which there are many at Wyoming Cemetery, have no markers. Catholics and Jews generally preferred to be buried at cemeteries for people of their own faith, and likely rest somewhere outside of Melrose. Fortunately, thanks to the tireless volunteers of findagrave.com, countless photos of gravestones have been uploaded and are fully searchable. Not all burials are represented there, but you are welcome to call Wyoming Cemetery directly so that they can check their complete records.

At this time of year, when the birds are singing and the flowers are in bloom, it is the perfect time to stroll through a local cemetery, and learn some history while you are there.